Trivia time! True or false: America On Line still exists.

Answer: True (well, false since it’s officially Aol – yes written like that – now). What the? Maybe the most surprising thing I gleaned from my research on last week’s quiz is the fact that AOL (screw you, I’m not writing it that way, marketers) is still around. For everyone over 30 this is surprising news. For everyone under 30 you will say “what the hell is AOL?” and so now, for the youngsters, I shall tell you a strange but true story from the proto-internet.

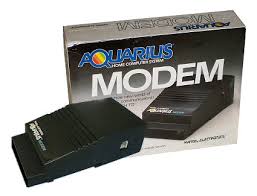

America Online started out as a company called Control Video Corporation back in 1983. Their business was pretty amazing… You would buy a modem from them, which at the time looked like this:

Now bear in mind that at the time, Radio Shack was advertising this product:

Which should give you a good sense of the level of technological sophistication we’re dealing with here. You would then hook your modem up to this, the famed Atari 2600 video game system:

Which remains a pretty fun gaming system, in spite of this atrocity of a game:

Developed in six weeks, this E.T. “game” was so overhyped and so perfectly unplayably bad that it more or less destroyed the entire home video gaming industry until Nintendo arrived on the scene. But that’s another story… Using your Control Video modem, you could download games for a dollar a piece, which would be playable until you turned your console off or disconnected from the network. I don’t even know how that could have been doable in 1983, and I guess it wasn’t, since the ventured failed.

Fast forward, and the company turned into America Online, which was a weird sort of ISP and more in the charming early days of the internet. At the time you had to actually dial in to an internet connection, such that every single time you wanted to search for the Anarchist Cookbook, you had to dial in and listen to this. Every time. And if anyone in your household tried to use the phone, or if you received a call, too bad! You’d get disconnected and have to start downloading that crappy Tae Kwan Do instructional web site all over again.

At this time AOL sold internet access, but also provided a strange sort of online community, with sites for kids, for teachers, and so on. This seems kind of odd to us, as we only really expect an internet service provider to get us onto the internet, where we can go do whatever we want. However, AOL’s early business model is reflective of the fact that the early internet sucked, because it was virtually empty. Therefore the company had a vested interest in both selling you access to the internet, but also providing you with a reason to want to be on the internet in the first place.

It was a fascinating time, actually, and looking back on that era you realize how totally corporatized the current internet is. Today, most – but not all – of the places you go online are operated by corporations who are either selling you their content or are selling you to their advertisers (never forget: if you’re not paying for the product you are the product). Google, YouTube, Twitter, the Gawker empire, newspapers, Imgur, Amazon, Facebook, and the platform you’re reading this on right now are all finely honed commercial enterprises. Even the so-called social aspects of today’s web largely consist of commenting on and sharing commercial products; liking and upvoting things is not content creation in a meaningful way (and yes I know that lots of people are making stuff online, I’m talking about the mass of users). This isn’t a criticism, either, simply an observation which contrasts with the nature of the early internet, where none of those outlets existed, and no one had any clue of how to make money off of your online activity.

The original internet consisted much more of individual people creating their own pages about things that interested them, often in a charmingly naive way (recall that reddit and wikipedia didn’t exist as hubs to share and grow knowledge). These pages were much more personal feeling, and didn’t try to be The Authoritative Source for a particular topic; they were usually more like “hey I like this thing, let me tell you about it”. If you wanted a cucumber salad recipe you didn’t go to Allrecipes and choose from their reviewed and annotated selection. No way; you stumbled blindly until you found Helen Bathgate’s Perfect Picnics Page and rolled the dice. Here are some great examples of these types of sites:

And for a real treat check out this tumblr, which posts old Geocities pages. It’s actually kind of sad to scores of such labours of love tossed on the electronic scrapheap. These people cared enough about Garfield, Duran Duran, and Baroque poetry enough to create these pages, and now they are lost forever.

For AOL, though, creating web content wasn’t always enough to drive people to subscribe. Sometimes they needed a little extra push to get them to dial the modem, and that’s where the infamous promotional discs came in.

Every now and again, with dependable frequency, you would receive a diskette or CD in the mail promising FREE INTERNET. All you had to do was put it in your computer… On the one hand you just knew there was a catch, but on the other hand, the temptation was incredible. This marketing tactic put everyone in North America with access to a credit card in the position of Adam and Eve staring up at those nice looking apples. Come on, jussssst try it. You will know everything! You’ll be connected to the entire world! It’sssssss free! And man, I can empathize with the urge to leave Eden.

Even at the time the potential of the internet was obvious to everyone, and breathless media reporting and futurism got way ahead of what the internet actually was. I would read the newspaper over cereal every morning and the excitement of the internet and what it was and would be was intoxicating. You could talk to people all over the world, buy anything, share your ideas with everyone on the planet, get books for free, and so much more. How could that not be alluring? And there it all was, on its way to being thrown out in a flimsy little envelope, sitting with the Columbia House deals on the cluttered table just inside your front door. For the younger set, imagine you’ve heard of Instagram and Tindr, but never seen them, and then someone sends them to you, in the mail. Think about that.

It was hard to understand your parents, who had an infinite amount of money with which they could buy anything, possibly saying no to all of this potential, and yet they did. Alas. I can still recall actually getting onto the internet for the first time at Marnie McCourty’s house. Here, son, you have access to all of humanity and its knowledge. With this great power I chose to download a picture of Lou Barlow, of one of my favourite bands.

The picture failed to finish downloading before Marnie was called to dinner and we had to leave. The real live online world of 1996 was considerably less exciting than I had been led to believe. It’s funny to wonder what you would do with the early internet, assuming that everything timely, useful, or well done is off limits.

AOL managed to rack up almost 30 million subscribers and became an absolute behemoth; its wave crested with the purchase of Time Warner, in 2000, for $164 billion (thanks to AOL’s ludicrous market capitalization, and in spite of Time Warner’s much larger assets and revenues – welcome to market capitalism, kids!). This deal – considered by many to be the worst in corporate history – is the canonical example of the synergistic fallacy, whereby two corporations spend mountains of cash to merge themselves because “hey you do this thing that complements this thing we do, and therefore a careful study of our potential for revenue growth shows that it is infinite.” Time Warner was a media company and AOL was a distribution channel for media, so it simply made sense that they should be one big, integrated company.

Vertical integration is an ever-swinging pendulum in all sorts of business, but none moreso than in the technology sphere, as companies routinely turn themselves inside out either acquiring or divesting of media content and distribution channels. Why the hell would Disney want to own an NHL hockey team in California? Vertical integration! We own the NHL team, we own the network that airs their games, we own the movie studio that makes the movies about the team from which the NHL team draws its name, we own the merchandising rights, and so on. Sometimes it works and sometimes it really doesn’t.

Then the dot com bubble exploded, and technology companies had to reckon with the fact that things like customers, revenues, and profits actually mattered more to investors than fanciful messianic scenarios which prophesied the wholesale dissolution of the economy as we knew it, to be replaced by an information golden age of limitless wealth, driven by an ethnic rainbow of people wearing khaki pants and colourful t-shirts working on laptops in coffee shops in metropolises around the world. Never mind who would actually operate those coffee shops or manufacture goods, or other pedestrian concerns. Only two years after the merger AOL Time Warner would write off a $99 billion loss, and AOL would see its market value drop off a cliff from over $200B to around $20B. American airwaves would soon fill with schills urging former tech employees who were now baristas to invest in gold bullion, because it never ever loses its value.

A funny thing, happened, though. AOL didn’t die. Having its tentacles in all sorts of business lines – with AIM Messenger, the Huffington media empire, an ISP business, MapQuest, and other stuff, you can think of them as a downmarket Google – actually allowed the company to survive and weather the storm of its declining dialup subscriber base.

However, they’re still charging those subscribers a fortune for I don’t even know what. I looked over AOL’s membership services, and in some instances they seem to be operating as an ISP, but some of their packages don’t actually include access to the internet. Instead, you can pay $7 a month for an AOL email address, and “virus scanning”. Even on their own site, what they do is not entirely obvious. A superficial reading might suggest that AOL grew up with the internet and carved out for itself a small media and advertising niche (they own the Huffington Post, Engadget, and some other things). However, a closer review seems to indicate that almost all of the company’s profits are driven by their entirely shady subscription base. In effect, they’ve finally understood the internet business enough to make money of off people who profoundly do not understand the internet business. I’ll state that again, because it’s so incredible: AOL appears to be a modern media company, save for the fact that its various media businesses consistently lose money. These losses notwithstanding, it actually makes money by selling subscriptions of seemingly no value, and has for years. This includes 2 million people paying them $20 a month for dial-up internet. It’s such a beautiful racket that I can’t but respect it. This article is a pretty amusing summary.

THE PROPHECY CAME TRUE

I am 35 years old, which situates me precisely on the internet event horizon. I was young enough when it came along that I adopted the internet without reservation, but I was old enough to remember what it was like beforehand, and what I thought about it at the time. My friend Godo somehow found us impossibly cool older girls (with cars!) to hang out with on New Dimensions, a Kingston Bulletin Board system (my user name was Quasimodo, and though I didn’t know it at the time, I was a troll). The idea of a BBS that included the whole world and that was free to use (you had to buy New Dimensions credits to say more than four things in the chatroom, which I never did) just blew my mind. Not to mention playing violent computer games against kids in foreign countries, or stealing movies via Africa and Sweden, or even writing articles, as I do now, in the hope that someone out there in the electronic ether might find it interesting.

The internet that we speculated about actually happened. You’re here with me now. It has engendered crushing loneliness and isolation. Twitter might just might be the scrolling suicide note of western civilization. But at the same time the internet of today is undeniably awesome. Truly. For those of us who remember what it wasn’t, way back when, it’s worth taking a moment to consider how cool it is to play bridge with people in Turkey, like my mom was doing the other day.

Still, the information age is not without down sides. Just last night my back yard dinner was interrupted by my precocious six-year-old neighbour Anna, whose hobbies include telling me things she’s learned and arguing with me (I’ve been trying for some time now to convince her that she is actually a werewolf). She informed me that in Egypt there are no cars, because it’s a desert. I suggested to her that the people there rode not only camels, but cars, trucks, and buses too. No way, she claimed. There are no cars in Egypt. And my instinct? Why, to whip out my phone, image search Cairo, and prove that, yes, the Egyptians do have cars. Take that, kid! I stopped myself on the way to my pocket, and remembered what it was like to have passionate arguments about the easily proven, in which both parties didn’t really know what they were talking about, and had no idea how to win the debate save to restate their views even more emphatically, or maybe through appeal to some equally ignorant third party. Such debates could last weeks, or even months, and were a genuine pastime for many, including me, and are impossible now.

I told Anna that we would agree to disagree about transportation in Egypt.

Just chiming in to say how much I love your posts. Informative, funny, and absolutely not trivial. Thanks!

LikeLike

Hey, thanks a lot! You made my day.

LikeLike

I had a GeoCities page. I even went out of my way to pick a nice round “address.” My obsession of choice was GoldenEye 007 for N64.

I remember the moment I thought things would be different. One of the neighbourhood kids casually mentioned (actual casual non-humblebrag mention) that he just got a cable modem. We dropped everything and went to his place to download something, anything. The download speed read 50 kilobytes per second (0.4 Mbps). We were amazed. Today LTE download speeds are 60x faster and you get it in your pocket and we use digital cameras as mirrors.

The first multiplayer game I played was with my buddy Tim. I called his modem from my modem. The game was “Modem 3D” which made some sense since perhaps multiplayer modem thing was its main feature. The game itself was like a first person tank game. It lasted a few minutes before someone picked up the phone. I ran into Tim like 15 years later at a Wal-Mart Auto Centre where he advised me to stay away from drugs.

Here’s what the game looked like. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ff8vlhWPsvg

Then there was the time my mom asked me about the huge long distance bill I had run up calling some BBS in the US. Woops.

LikeLike

You made me realize that I, too, miss the ability to have extended ignorant debates. I also miss a sense of mystery with music. Liking a not-too-popular band and wondering what they had previously released, but not being able to find out. Randomly finding a record by a group that you like in a used record store, not previously knowing that it even existed. Going to a book store to look at one of those expensive music discography books, and finding out that some band had numerous early albums that I did not know existed. Then going home and wondering what they sounded like, since I couldn’t just download them instantly. And not actually hearing the albums for many, many years. Or being super excited to actually find the elusive record on a trip to Toronto.

It is pretty awesome to be able to hear almost any music that I want to hear in an instant, but I do miss some of the mystery and excitement of the past.

LikeLike